The humanities’ Fallen (read: academics who aren’t actively in a college or university department), like myself, tend to preen themselves, in order to prop up their self esteem, with their personal libraries. I obsess over my academic bookcase. Every few months, I’ll make sure the books are in a particular order: chronological? alphabetical? thematic? Must… re-sort… them!

It’s a cleansing of the palate. A taste of ginger amongst the sushi buffet. Upon the occasions that I have moved, books do get lost or given away, but it’s important to see it as a pruning of the tree; not a cutting-off of fingers (or worse, the abandonment of children). In fact, one learns from the Greeks that the exposure of children to the elements will only undo you in the end (e.g., Oedipus).

But the arrangement of books offers the opportunity for new perspective. Most recently, I combined my entire library chronological, starting from Gilgamesh to my latest issues of the Paris Review, fiction and non-fiction intertwined. And to see the literature and history of a particular point in time (and various arcs of time) is stunning.

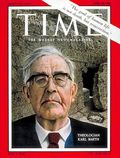

For instance, my (not-quite complete set of) The Church Dogmatics of Karl Barth, the influential Swiss Reformed theologian, shares the same shelf as William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch.

For instance, my (not-quite complete set of) The Church Dogmatics of Karl Barth, the influential Swiss Reformed theologian, shares the same shelf as William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch.  Both appear in their relatively completed forms in 1962, the year of the Cuban Missile Crisis and the release of The Beatles’ “Love Me Do.” Culturally, it was an important year. A very subversive year. This is the year that the Roman Catholic Church’s Second Vatican Council ended. Barth, who attended Vatican II, upended Protestant theology. Institutional religion went through major, liberalizing changes. We remember the latter half of the decade, but we forget that the real work, the real subversion, happened earlier. Barth and Burroughs rethink the whole project. They take their respective institutions of religion and literature, and rethink them (and themselves) entirely.

Both appear in their relatively completed forms in 1962, the year of the Cuban Missile Crisis and the release of The Beatles’ “Love Me Do.” Culturally, it was an important year. A very subversive year. This is the year that the Roman Catholic Church’s Second Vatican Council ended. Barth, who attended Vatican II, upended Protestant theology. Institutional religion went through major, liberalizing changes. We remember the latter half of the decade, but we forget that the real work, the real subversion, happened earlier. Barth and Burroughs rethink the whole project. They take their respective institutions of religion and literature, and rethink them (and themselves) entirely.

God and Literature are exploded, liberated, broken out of their frames, rupturing, exploding, liberating what can be read and understood. Barth, as majestic and comprehensive as his work is (for those who appreciate it) is as obscene as Burroughs (for those who appreciate it) – as all creativity is obscene.

The irony is that both Barth and Burroughs are now part of the canon, institutionalized by us academics who put them on (separate) shelves. And by putting them on these pedestals, we forget how dirty they are, how they are a kick in the balls of propriety and the status quo. It is so like us to canonize, beatify, and sanctify our rebels. And in doing so, we do them a disservice.

Saints Barth and Burroughs? Really? Yeah, really. You, who’ve canonized them. You know who you are. Because I’ve done it, too. And we’re all sellouts for it.

We must remember our saints for who they are: rough and tumble subversives who gave the finger to their worlds and leaders. And their legacies must continue to disrupt. Barth and Burroughs are easy allies on my shelf because they unravel the books around them. And they, themselves, unravel themselves. Such are the lives of subversives. Funny how Barth and Burroughs lived so long… They actually got to see what the worlds they upended became.

How obscene is that?