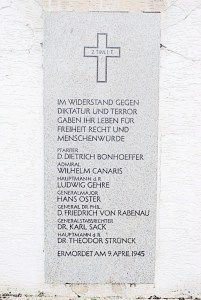

In the early hours of this morning at the Flossenbürg concentration camp, Dietrich Bonhoeffer was led to the gallows among Nazi guards and hanged until he was dead. It was not Palm Sunday seventy-two years ago. In fact, Easter fell on April Fool’s Day in 1945. Today, Jesus is led into the streets among joyful revelers that will turn on him in less than a week. He will be hung on a tree until he is dead.

In the early hours of this morning at the Flossenbürg concentration camp, Dietrich Bonhoeffer was led to the gallows among Nazi guards and hanged until he was dead. It was not Palm Sunday seventy-two years ago. In fact, Easter fell on April Fool’s Day in 1945. Today, Jesus is led into the streets among joyful revelers that will turn on him in less than a week. He will be hung on a tree until he is dead.

“When Christ calls a man,” Bonhoeffer famously writes in The Cost of Discipleship, “he bids him come and die.” Bonhoeffer did not seek martyrdom, but only to preach the Gospel, which ultimately found its expression in his complex and stark theology of religionless Christianity. And yet here he was in a jail cell, caught up in one of countless Nazi dragnets seeking out resistors. His last words before the gallows were “Das ist das Ende – für mich der Beginn des Lebens.” And then the floor fell out beneath him.

This week is always complex and stark. An entire religion in stark relief about how things are and where things stand. The Early Church did not care about Christmas. It was not the matter of incarnation that ultimately concerned it. It was the matters of death and resurrection. Christmas is a mere affectation, something to satisfy those who need a beginning of the story. Because the story is really about the story’s end and the paradox of how it refuses to remain over. This is the end and the beginning.

This week starts with cruel irony, a day of joy and adulation to end on a Saturday of absence and void. Every Christian, no matter how nominal, two millennia across, stands in today’s Jerusalem crowd. Today, the Church stands in solidarity, to be absent on Friday. Bonhoeffer, too, is in the crowd. As harsh as it sounds, it’s where he belongs, where we all belong. But we are only human. But there in the loud din of “Hosannah” and “Glory to the highest!”, Jesus bids us quietly to come and die. He is on the way, there in Jerusalem. Come follow. On Friday, we will say, “No. You go alone.” On Sunday, we have to wrestle with our answer in face of the proclamation of otherwise. What shall we do? How shall we live? Who shall we become?

Like all martyrs, Bonhoeffer has had to suffer the fate of being transformed into a wax nose, an object to be molded and fashioned to each person’s, each agenda’s liking. In recent years, Evangelicals have sought to transform him into a mirror of themselves, much to the horror and chagrin of Bonhoeffer’s scholars. But all good saints trouble such idolatry. Bonhoeffer’s life and death and legacy ultimately resists such joy and adulation. He is a man on his way to his executioners, those who seek to annihilate who he is and who seek to transform him into their understanding of him, something controllable and lifeless, something that will suffer rigor mortis and remain as they desire.

Palm Sunday is that beginning of a week-long walk to the Tegel gallows, to the Place of the Skull, Golgotha. How can we possibly walk with Bonhoeffer to the noose today? How can we possibly walk with Jesus from the gates of Jerusalem? We are bidden to come and die and for what? Those who say “yes!” so quickly are the worst of the revelers of Palm Sunday. Beware of them and do not follow them. Palm Sunday is our day when we remember why we can’t have nice things, but are ultimately, because of grace, given them, anyway.